As teenagers who are sorting out and deciding what we want to do with our lives, it can be hard to pinpoint one passion to pursue. There are plenty of choices to make regarding going to college or joining the workforce, what to major in or what work field to chose, and what school or job is the best fit for you. It is hard to pick between what we know we enjoy and what could support our long-term.

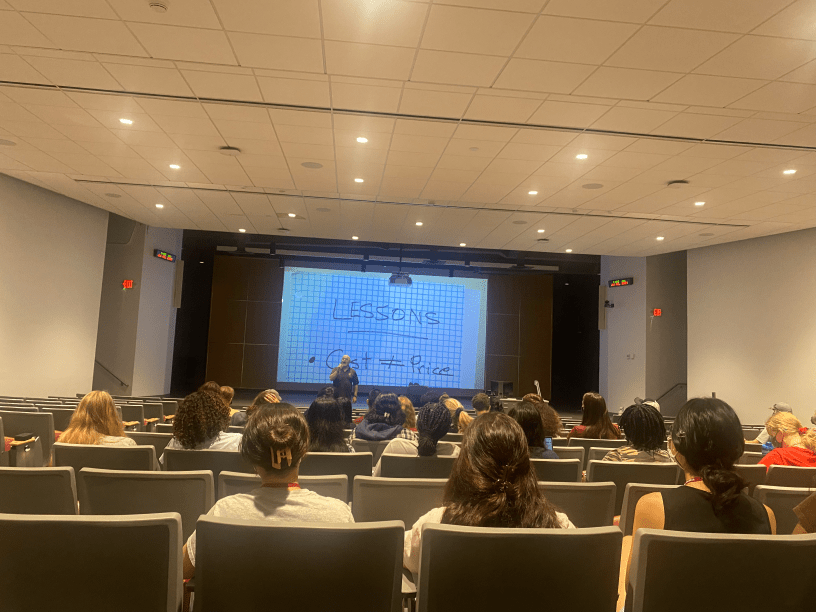

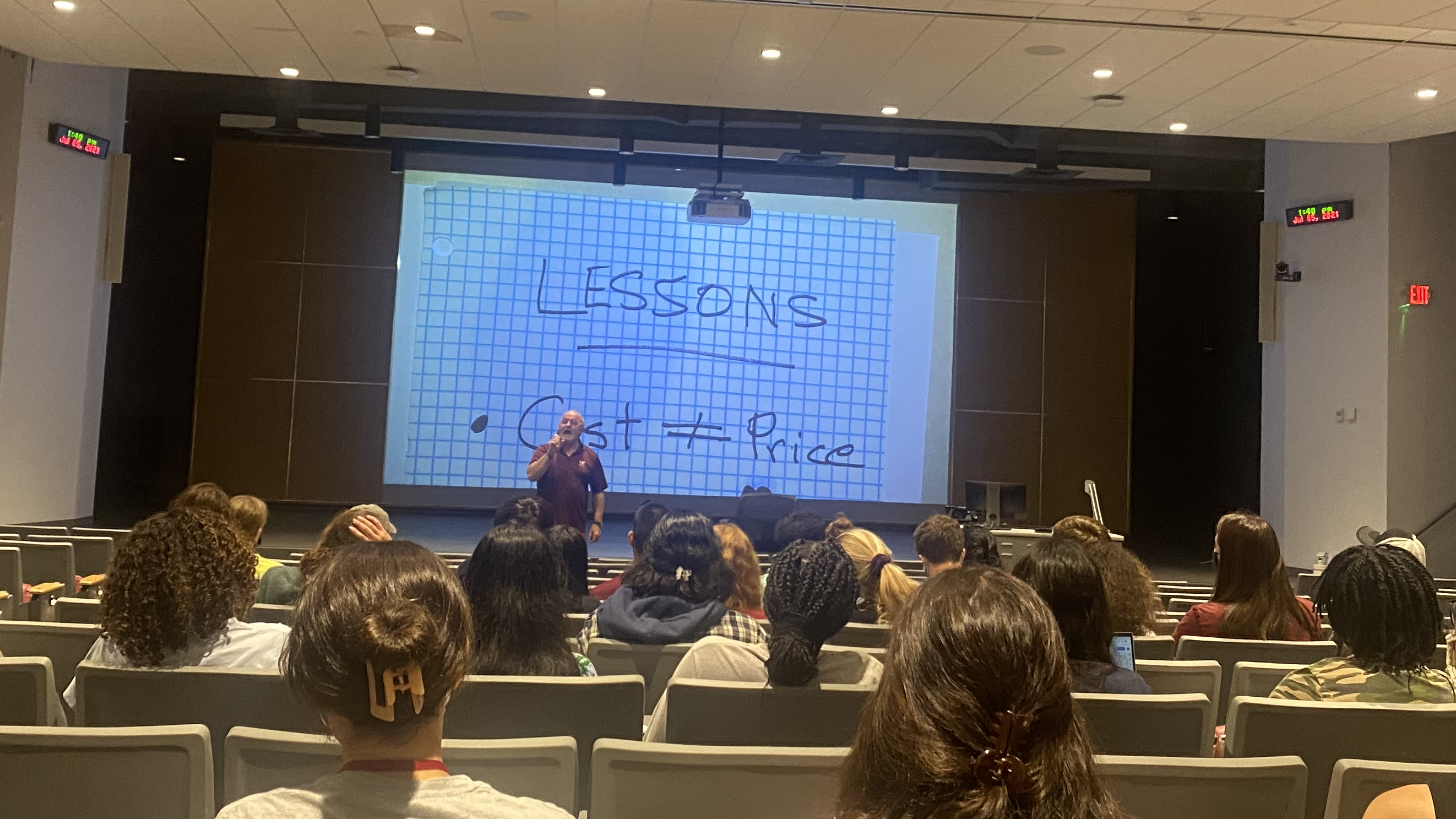

Today in our economics class, Mike Ellerbrock told us something that puts into perspective the upcoming decisions we have to make regarding our future. He taught us about the Principle of Comparative Advantage.

At first, when he said this, I sat there confused. I didn’t understand where our passions and future jobs came into play. Then he explained the difference between absolute advantage and comparative advantage. Absolute advantage is what you do best by yourself, and comparative advantage is what you do best compared to the competition.

Mike’s example was Mike Vick. For his example with Mike, he said, “You are a football coach who has Mike Vick, an A+ quarterback on your team. He was made to be a quarterback. The only person on your team who is a good receiver is also Mike Vick. Your backup quarterback is a solid B quarterback. And lastly, your goal as a coach is to win as many football games as you can. Who do you put as your quarterback?” The answer was the B-grade backup quarterback. In the end, although Mike Vick is the best quarterback this coach has ever seen; in order for his team to win, Mike Vick has to play wide receiver. His absolute advantage is being a quarterback, but his comparative advantage is being a wide receiver in this scenario.

Mike ties this into how we will decide what to major in, what workforce to go into, and what passions we will pursue throughout our lives. We have to think about our comparative advantage versus our absolute advantage. Our passions in life that we grew up on may not financially support us, and we might have to pursue something else until we have the means to go back to our absolute advantage. In the end, economics can help us realize what to pursue at the moment or which direction we should take with our futures’.

-mm